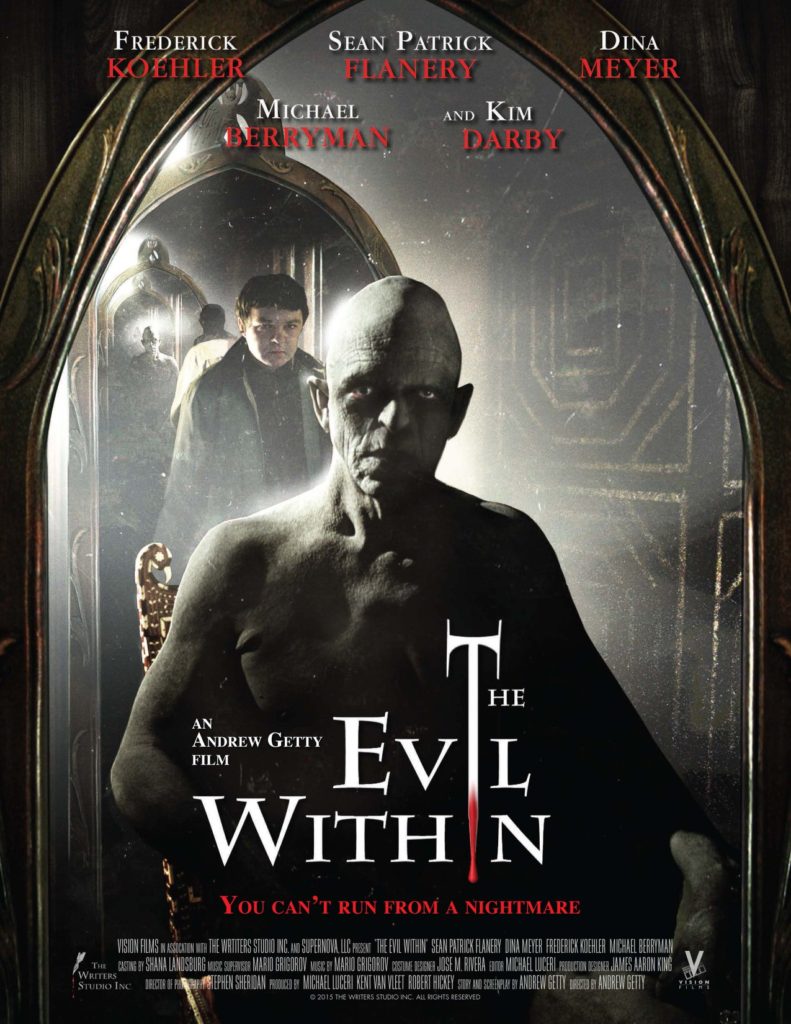

THE EVIL WITHIN

Some films are destined to be more than the sum of their parts: the story behind them proves more fascinating than the actual movie itself. Such is the case with The Evil Within — although a strong case could be made that the film itself is as bizarre as the journey to make it.

Written and directed by Andrew Getty, The Evil Within follows a mentally challenged young man who is attacked, beguiled and manipulated by a demonic presence in an antique mirror. The demon sometimes takes the form of Michael Berryman (best known for being the mugshot on The Hills Have Eyes poster) but sometimes the demon just appears as the kid’s doppelganger, taunting him from the other side of the mirror. Like the Son of Sam, the kid rails against the entity’s orders but finds himself in a jet-propelled nosedive to the bottom of the sanity barrel.

Directed by Andrew Getty — the grandson of a real-life oil baron —The Evil Within was shot over a 15-year period. Getty mostly financed the movie’s budget of $6 million through his family fortune, but finishing finances, creative differences and actors’ schedules still managed to stagger the project. Getty got the idea for the project from his own personal nightmares. His own real-life nightmare would become a reality when he died of an ulcer caused by methamphetamine and heart disease while trying to perfect his homemade effects.

The film is a complete paradox. It’s not exactly bad, but it’s not exactly good either. The acting is often rushed by its professionals (there’s a really bad exchange between Sean Patrick Flannery and Kim Darby) but often compelling when the mentally challenged character (Frederick Koehler) argues against himself. It has an amateur, video feel to it but often succeeds in being completely imaginative and cinematic in style. In fact, some of the techniques found in the opening and last sequences are brilliant but bafflingly crude. I found it intensely hypnotizing — at least for the first 45 minutes and the last ten.

The Evil Within is a rare unicorn. A self-financed vanity project that is honest in its origins and intent but a bit too bizarre and unrefined to be a really good cult find (like Panos Cosmatos’ superior Mandy). Still, it makes this old cinema hound happy that in this day-and-age of controlling executives and marketing conglomerates, something like The Evil Within can still exist.